Scientists have found that a single microbial species can blunt the negative effects of a high-fat diet due to the unique mix of lipids it produces [1]. They intend to identify its specific lipids in future work.

Good neighbors

The billions of gut microbes that we share our bodies with can profoundly influence our health. For instance, microbiome diversity is generally reduced in obese people [2]. Transferring microbiota from obese to lean mice causes the latter to put on weight [3], while entirely germ-free mice stay lean under a high-fat diet (HFD) [4], suggesting that some bacteria promote weight gain while others restrict it.

Scientists have known for a while that spore-forming (SF) bacteria support healthy metabolism and leanness. The team at the University of Utah that originally discovered this connection recently looked for particular bacterial strains that can produce an oversized effect, and they published their result in Cell Metabolism.

The lone hero

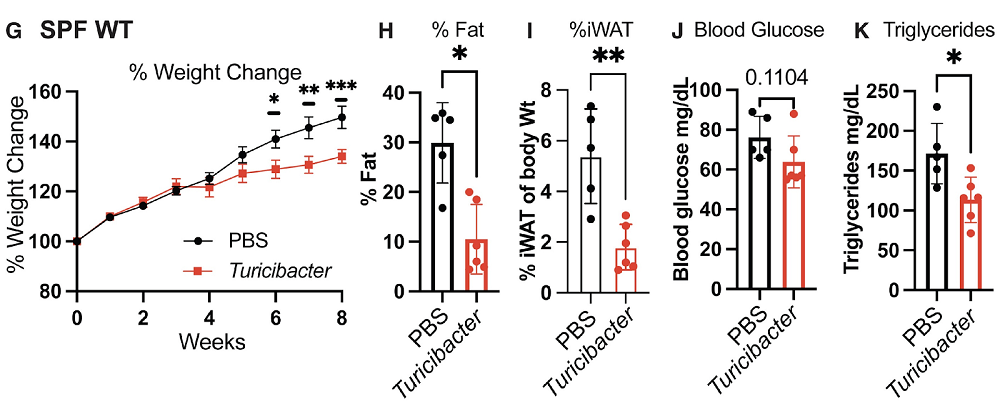

The researchers found that among all the SF species, the bacterium Turicibacter single-handedly improved the metabolic health of mice on HFD when supplied continuously, including lowering triglyceride levels more robustly than the entire SF community. Turicibacter also reduced weight gain and shrank white adipose tissue (WAT). It pushed down sphingolipid metabolism in the small intestine and lowered circulating ceramides. Ceramides, a subclass of sphingolipids, tend to rise on HFD and are often linked to insulin resistance and lipid overload.

“I didn’t think one microbe would have such a dramatic effect; I thought it would be a mix of three or four,” said June Round, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology at U of U Health and senior author on the paper. “So when [we did] the first experiment with Turicibacter and the mice were staying really lean, I was like, ‘This is so amazing.’ It’s pretty exciting when you see those types of results.”

The team then used a human metagenomic database to compare Turicibacter levels across people categorized by obesity status. In that dataset, Turicibacter was markedly lower in individuals with obesity, which matches several prior studies.

As HFD in mice is also associated with reduced microbial diversity, the researchers hypothesized that diet might directly suppress Turicibacter, rather than the latter simply being a passive marker of obesity. To prove this, they used Turicibacter-monocolonized mice (germ-free mice colonized with Turicibacter alone), feeding them either HFD or normal chow. HFD almost eliminated Turicibacter from the small intestine and significantly reduced it in the lower GI tract, despite it being the only organism in the gut. Interestingly, palmitate, a major saturated fat in HFD, reduced Turicibacter growth in vitro.

These results suggest that HFD may promote weight gain in part by suppressing the bacteria that normally counteract it. Since HFD is hostile to stable colonization, in the in vivo experiments, the mice had to be not only monocolonized with Turicibacter but also constantly fed it to keep them exposed to the bacteria.

The secret is in the mix

Using bacterial lipidomics, the researchers showed that Turicibacter produces a highly specific mix of lipids dominated by galactolipids with relatively low phosphatidylcholine. They note, however, that 95% of the Turicibacter lipidome is unannotated, so it could be making sphingolipid-like molecules that current databases miss.

Importantly, experiments showed that lipids from Turicibacter can get into intestinal epithelial cells. Once there, they downregulate genes that support ceramide synthesis. The team suggests that this slowing down of ceramide production, which leads to reduced fatty acid uptake by epithelial cells, is likely a major contributor to the bacterium’s effect on weight gain. Apparently, HFD does not just reduce Turicibacter abundance, it also shifts its lipid composition, blunting its effect on ceramide synthesis.

Treating epithelial cells with Turicibacter-derived lipids in vitro recapitulated the bacterium’s effect on lipid uptake. When this lipid extract was fed to mice, the animals showed reduced weight gain, lower fasting glucose, lower WAT, and blunted sphingolipid-related gene expression.

Next, the researchers hope to identify the particular lipids responsible. “Identifying what lipid is having this effect is going to be one of the most important future directions,” Round said, “both from a scientific perspective because we want to understand how it works, and from a therapeutic standpoint. Perhaps we could use this bacterial lipid, which we know really doesn’t have a lot of side effects because people have it in their guts, as a way to keep a healthy weight.”

“With further investigation of individual microbes, we will be able to make microbes into medicine and find bacteria that are safe to create a consortium of different bugs that people with different diseases might be lacking,” said Kendra Klag, PhD, MD candidate at the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine at the University of Utah and first author of the paper. “Microbes are the ultimate wealth of drug discovery. We just know the very tip of the iceberg of what all these different bacterial products can do.”

Literature

[1] Klag, K., Ott, D., Tippetts, T. S., Nicolson, R. J., Tatum, S. M., Bauer, K. M., … & Round, J. L. (2025). Dietary fat disrupts a commensal-host lipid network that promotes metabolic health. Cell Metabolism.

[2] Davis, C. D. (2016). The gut microbiome and its role in obesity. Nutrition today, 51(4), 167-174.

[3] Ridaura, V. K., Faith, J. J., Rey, F. E., Cheng, J., Duncan, A. E., Kau, A. L., … & Gordon, J. I. (2013). Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science, 341(6150), 1241214.

[4] Bäckhed, F., Manchester, J. K., Semenkovich, C. F., & Gordon, J. I. (2007). Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(3), 979-984.

View the article at lifespan.io